Russian-Ukrainian War Update: Will Crumbling Attrition Lead to a Return of Maneuver Warfare

I last commented on the Russian-Ukrainian war about eight months ago. In that article I speculated on whether or not a breakthrough of the first Ukrainian defensive line in the Donbas would lead to a Russian breakout. That could have meant a potential return to the sweeping war of maneuver that had characterized the initial weeks of the Russian invasion (or "special military operation"). Since then quite a bit has changed, not least of which is a reappraisal of Russia's methodology for fighting this war.

Just to recap, Russia opened the war in February by invading with a small force of around 150,000 men from the Russian regular army and national guard. They were supported by approximately 50,000 men from the Donetsk/Luhansk Republics. The latter represented the primary force fighting to take over the entirety of the Donbas, so they are really a localized combat grouping. The numbers here are in dispute, but most reliable observers are convinced the total was fewer than 200,000 men deployed in total by the Russians. It appears that in retrospect the initial wide spread thrust of the Russian armed forces may have been meant to induce a quick political collapse of the Ukrainian regime. By all accounts this was happening. But then the U.S. and NATO (really the U.S. here through the Brits) made sure the Ukrainians understood there would be no negotiated end to the open warfare that had broken out - warfare that had been simmering along since 2014 (but largely confined to the Donbas).

At that point, the Russian regular army pulled back from its penetrations near Kiev and Kharkov, while holding onto a bridgehead over the Dnieper River near Kherson (the southwestern most point in a line of contact stretching all the way to the east and northeast, through the Donbas, and up to positions east of Kharkov). From there, the main body of the Russian army transitioned to an economy of force operation. This transition caught me off-guard at the time I last wrote on the war (in May).

At that time I expected the Russians to be simply redeploying for another stab at a wide sweeping operational maneuver - perhaps one fueled by the breakthroughs achieved of the first Ukrainian defensive lines in Donetsk and the taking of most of Luhansk. Note that the small portion of the Russian regular army deployed into the Ukraine played an important role in breaching these defenses. By the summer the Ukrainians had seen much of their pre-war army destroyed, but the Russians had also been dealt a bloody nose. To this date no one knows the exact casualty figures on each side, but it is fair to say that losses on the Russian side were less than the Ukrainian; but still fairly significant during these initial months leading into the summer of 2022. As a result, from a Russian perspective there simply wasn't the force ratio's then available to return to a war of maneuver.

I didn't recognize that reality and was more than a little surprised at how under resourced the initial Russian attacks really were. Part of my confusion may have stemmed from my decision to overlook Putin's actual justification for the war regarding demilitarizing and de-nazifying the Ukraine. It appears that those are real goals of the Russian military operation, and not just red meat for the Russian people. It took me a long time to realize the Russians were content to bleed out the Ukrainians, and drain NATO of its stocks of available weaponry as a core strategic objective prior to whatever was to come next.

I was also thrown by the fact that the main body of the Russian army was largely a secondary player by the late summer. Remember, since the first phase of the war ended, the bulk of the professional Russian army involved in the fighting pulled back to reset. Most of the heavy lifting on the ground in the Donbas has been conducted by Russian mercenaries (the infamous "Wagner Group"), the aforementioned mobilized manpower from the Donetsk/Luhansk Republics, and secondary Russian forces. This is not to say the regular Russian armed forces haven't been involved, far from it. They have been providing massive support (particularly in terms of long-fire firepower) to the aforementioned hodge-podge of units in the Donbas. In addition, Russian airpower has been heavily involved in the war, and Russian regular army units have also been involved in the fighting (just not en masse).

Elsewhere and late in the summer/early fall of 2022 the Ukrainians finally went on the offensive. The results were politically embarassing for the Russians. The Ukrainians ended up retaking territory Russian forces had only acquired at great cost in the spring - paticularly at Izium. Ceding that territory back did not sit well with most Russians.

But, achieving that outcome was militarily disastrous for the Ukrainians. That's because for most of the summer the professional core of the Ukrainian army had been painstakingly retrained and re-equipped by NATO. These forces were then sent to attack Russian lines east of Kharkov and the bridgehead at Kherson. As to the former, the Russian lines there weren't really lines at all, but a smattering of police and national guard troops. They simply withdrew to defensible lines further east. Meanwhile, the Ukrainians, having now deployed into the open, were (by all accounts) absolutely pounded by Russian artillery and airpower. As a result, those attacks quickly culminated once the Ukrainians ran up against prepared Russian defenses.

A similar process unfolded near Kherson, just over a greater period of time. In both cases Russian casualties were minor, and both counter-offensives ultimately led to the destruction of the Ukrainian operational reserves. From there, the Russian troops redeployed into shorter and more defensible lines (having traded space to preserve their forces). Meanwhile, the fall-out of these "defeats" was politically expeditious for the Russian leadership. It allowed them to take the stronger measures needed. That took the form of a two-fold response.

First, a partial mobilization was finally called. By October of 2022, and for the first time in the war the Russian army deployed at the front had achieved rough numerical parity with what had been a much larger Ukrainian army. The Russians spent the fall of 2022 training new recruits, re-organizing existing forces, and re-equipping. Needless to say the Russian army facing off against the remnants of the Ukrainian army here in January of 2023 represents a far more potent army. One fully ready to go back to a mobile war if it so chooses.

The second part of the Russian response to the Ukrainian counter-offensives was to finally take the gloves off and seriously degrade Ukrainian infrastructure (as well as pounding military targets throughout the Ukraine). This effort took the form of a long-range missile bombardment that by the end of 2022 had crippled Ukrainian electrical output and the rail network. This is important. Both the Russian and Ukrainian militaries are logistically dependent on their rail lines. The Ukrainian army's mobility has been further denuded as a result of this bombardment.

Meanwhile, a first world war style attritional battle has been methodically maintained by the Russian armed forces in the Donbas. The prime goal here appears to be simply to suck in and decimate the Ukrainian forces where they sit in their fixed fortifications. It appears this has succeeded as well. By all reasonable accounts this has been a Ukrainian bloodbath, with Russia's advantages in long-range firepower inflicting large losses on the regular Ukrainian army. Worse yet for the Ukrainians, the primary Russian assault troops during this battle have not been the Russian army itself; but the Wagner Group and local forces in the Donbas (i.e. forces that would play a secondary role in a combined-arms mobile war).

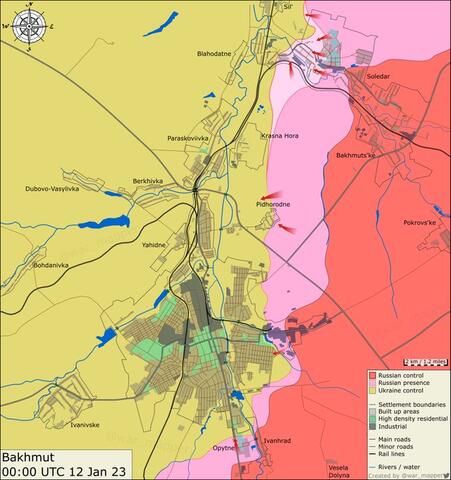

Before we get to the takeaway of all of this, I will say that I have no idea what the Russians are going to do next. But I will speculate. The most important factor to look at here are the current means the respective army's have at their disposal to accomplish their goals. The regular Russian army is stronger than it has been since the war began almost one year ago. The Ukrainian army is in dire condition, having been forced to fight on Russian terms for months and at great loss. As I write this, the second Ukrainian defensive line in the Donbas is crumbling (with Soledar likely having fallen and Bakhmut in extreme danger of being next - see map courtesy of War Mapper on Twitter). This is extremely problematic for the Ukrainians, who are largely dependent upon the stout defensive lines in this region until further outside help arrives.

But will it? Or, more to the point, will it arrive in an operationally signficant manner?

Most NATO stocks of available equipment have been destroyed. Yes, there have been recent pledges being made by NATO countries of new batches of IFV's, and even MBT's for the Ukraine, but they are in operationally insignificant amounts. What the Ukrainians need are hundreds of AFV's, as well as a whole host of other weapons (especially artillery), along with the time to train their latest recruits to fight a combined arms war of maneuver. The lack of such an equipped and trained army is part of the reason why the Ukrainians have entrenched themselves in World War I style trenches, fortifications, and in cities. If they have to face the Russian army in the open then the Ukrainian army as it presently exists will get slaughtered. But entrenching themselves hasn't helped much either. It simply means it takes the Russians longer to identify the defensive strongpoints and then eliminate them (most commonly via drone adjusted artillery fire). All-in-all it's a horrible position for an army to be in - either die in place slowly, or fight in the open and get crushed more quickly.

More troubling yet, Gerasimov has replaced Surovikin in command of the Russian forces. Surovikin's job was to shape the battlefield for whatever is coming next - he accomplished that goal. In contrast, Gerasimov is a Deep Operations-tank-infantry-artillery-ground-war-of-movement style commander. And again, the ground is frozen. The Russians now have the means to launch one major, or perhaps even two, deep operational strikes. Will they? If they do I am at a loss as to how the Ukrainians can effectively respond absent massive NATO reinforcement. I lean toward believing the Russians will act soon, and launch a major offensive. But...

The Russians could continue to fight a war of attrition and slowly bleed the Ukrainians to death. If the latter happens it will give the Ukrainians time to equip (only possible with NATO stocks) and train reserves capable of fighting a mobile war by the late spring or early summer. But by that point I would think even an ongoing Russian attritional approach will have taken the bulk of the Donbas. And if this third Ukrainian army (the first two having been destroyed already) faces the rebuilt Russian army out in the open...well, you can probably surmise that I don't like Ukrainian chances at all in such a fight.

Post new comment