The Big Red One in Czechoslovakia 1945

By Bryan J. Dickerson*

Of all the U.S. Army units to serve in Czechoslovakia during 1945, none was as combat experienced as the 1st Infantry Division. From the assault landing at Oran, Algeria on 8 November 1942 to V-E Day in north-west Czechoslovakia on 8 May 1945, the “Big Red One” spent an astonishing 443 days in combat across two continents. As World War Two in Europe came to a close, the 1st Infantry Division was heavily reinforced with the 406th Field Artillery Group and Combat Command ‘A’ of the 9th Armored Division; all designed to help the “Big Red One’s” important role in one of the final Allied offensives in the European Theater.

The Early Years of the Big Red One

The 1st Infantry Division was originally formed on 8 June 1917 and was organized around four infantry regiments and three field artillery regiments. Deployed to France in December 1917, the 1st Infantry Division fought with distinction in such battles as Cantigny, Soissons, St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne. It was during the war, that the division adopted its nickname “the Big Red One” from its shoulder patch – a red number one on a green pentagon. After the Armistice halted fighting on 11 November 1918, the 1st Division served on occupation duties in Germany before returning to the United States. In the massive rapid demobilization of the U.S. Army following the end of World War One, the 1st Division was fortunate to survive as one of only four Army divisions on Active Duty. In early 1940, the division was re-named as the 1st Infantry Division and re-organized under the “triangle” system which eliminated one of the division’s four infantry regiments.[1]

The Big Red One in World War Two

When the U.S. entered World War Two in December 1941, the 1st Infantry Division was stationed at Fort Devens, Massachusetts. The following August, the division deployed to Great Britain and from there, embarked aboard ships for Operation Torch – the invasion of North Africa. On 8 November 1942, the Big Red One landed at Oran, Algeria. The division fought in the North Africa campaigns of 1942-1943. Then in July 1943, the division participated in the invasion of Sicily as part of General George S. Patton Jr’s Seventh U.S. Army. The following November, the division was sent back to England to prepare for the Allied invasion of Normandy – codenamed Operation Overlord.[2]

On 6 June 1944, the 1st Infantry Division and the 29th Infantry Division stormed ashore on the Norman coast of France on a long beach codenamed Omaha Beach by the Allies and stretching between Point du Hoc to the west and Colleville to the east. The fighting on Omaha Beach was the fiercest fighting of that witnessed on any of the five Allied invasion beaches on that pivotal day. After securing the beachhead, the 1st Infantry Division fought through the hedgerows of Normandy and participated in the pursuit of the German Army across France. By September, the division was attacking the German frontier defenses known as the Siegfried Line. In mid-October 1944, the Big Red One captured the city of Aachen – the first German city to fall to the Allies. Afterwards, the division attacked through the Hurtgen Forest and reached the Roer River.[3]

The 1st Infantry Division had taken substantial casualties in the fighting in the Hurtgen Forest. On December 16, 1944 the division was in a rest area east of Liege, Belgium when the Germans launched their massive surprise counter-offensive known forever since in the U.S. as “The Battle of the Bulge” – the greatest battle the U.S. Army fought in World War II. The division hurried south as one of the U.S. divisions called upon to repel the German onslaught and held a critical sector on the northern shoulder of the ‘Bulge.’[4]

After the Battle of the Bulge, the 1st Infantry Division attacked across the Roer River and drove to the Rhine River. Crossing the Rhine River at the Remagen bridgehead secured by the 9th Armored Division, the 1st Infantry Division participated in the encirclement and reduction of the Ruhr, drove across central Germany, and cleared the Harz Mountains region. At the end of April 1945, the division was moved into position on the left flank of the 97th Infantry Division which was then operating along the German – Czechoslovak border of 1937.[5]

The 1st Infantry Division Order of Battle – Czechoslovak Operations[6]

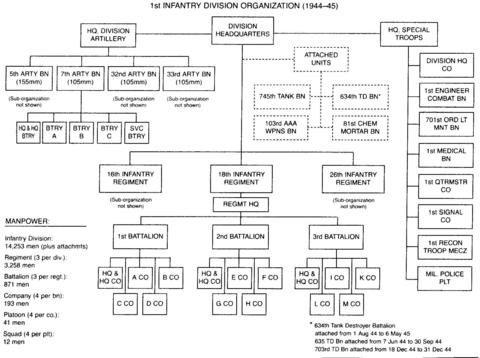

The 1st Infantry Division was organized and equipped under the U.S. Army’s standard Table of Organization and Equipment for infantry divisions. Accordingly the 1st Infantry Division consisted of:

· Division Headquarters / Headquarters Company

· 16th, 18th and 26th Infantry Regiments

· 1st Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

· 1st Engineer Combat Battalion

· 1st Medical Battalion

· 1st Division Artillery: 5th, 7th, 32nd, and 33rd Field Artillery Battalions

· 701st Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

· 1st Quartermaster Company

· 1st Signal Company

· Military Police Platoon

· Division Band

Also per standard procedures, the division was reinforced with a variety of attachments. For the Czechoslovak operation, the division also included:

· 745th Tank Battalion

· 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Self-Propelled)

· 103rd Anti-aircraft Artillery (Automatic Weapons) Battalion (Self-Propelled)

· 406th Field Artillery Group

o 76th, 186th , 200th, and 955th Field Artillery Battalions

o 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion[7]

With the attachment of the 406th Field Artillery Group, the 1st Infantry Division had a total of eight battalions of field artillery. In addition, each infantry regiment had its own Cannon Company equipped with with short barreled 105mm howitzers.

Under standard U.S. Army organization, infantry divisions did not have armored units as part of their organic force. Instead they were augmented by independent battalions attached as needed. In practice, most attached tank and tank destroyer battalions remained with their assigned infantry divisions throughout the European Campaign. The 1st Infantry Division’s attached armored support was provided by the 745th Tank Battalion and the 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Like their counter-parts in other U.S. infantry divisions, the companies of these battalions were attached to support the infantry regiments and as such fought as part of a combined arms team operationally separate from their parent battalion.

The 745th Tank Battalion was commanded by LtCol Wallace J. Nichols. The battalion consisted of a Headquarters Company, a Service Company, three companies of M4 Sherman medium tanks and a company of light tanks. The battalion had landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day and been supporting the 1st Infantry Division since Normandy.[8]

The 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Self-Propelled) was commanded by LtCol Henry L. Davisson. It consisted of a Headquarters Company, a Reconnaissance Company and three companies equipped with M10 tank destroyers. These lightly armored tracked vehicles mounted a 3-inch gun in an open topped turret. The battalion had been supporting the 1st Infantry Division since Normandy.[9]

The most significant attachment for the Czechoslovak operation was Combat Command A of the 9th Armored Division. While most of the 9th Armored Division would be held as V Corps’s reserve, CCA would constitute a powerful armored striking force for the 1st Infantry Division. CCA 9th Armored Division consisted of:

· Headquarters and Headquarters Company / Combat Command A

· 60th Armored Infantry Battalion

· 14th Tank Battalion

· 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion

· Attachments from –

o 2nd Armored Medical Battalion,

o 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion

o 482nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion (Self-Propelled)

o 131st Armored Ordnance Maintenance Battalion

o 9th Armored Engineer Battalion

o 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron [Mechanized][10]

The Men of the 1st Infantry Division

In early May 1945, the 1st Infantry Division was one of the most experienced combat units in the U.S. Army. The division had previously been commanded by Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, and Major General Clarence R. Huebner. Major General Allen was now the commanding general of the 104th Infantry Division, at that time located near the Mulde River. Major General Huebner had been promoted to commanding general of the V Corps, of which the 1st Infantry Division was now a part. The division’s commanding general was Major General Clift Andrus, who had formerly served as commander of Division Artillery.[11]

Having experienced many months of heavy combat, and the large turnover of personnel due to that combat, the 1st Infantry Division had a mixture of both soldiers who had served with the division since North Africa and newly joined replacements. Staff Sergeant William Laird of Headquarters Battery, 5th Field Artillery Battalion, had joined the 1st Infantry Division in October of 1940 and fought with the division from North Africa and Sicily right through the European Campaigns. The Big Red One’s G-5 (Civil Affairs) Officer Lt Col Thomas F. Lancer had been a New York State Trooper and an FBI agent before the war. He resigned from the FBI after the Germans invaded Poland and was assigned to the 7th Field Artillery Regiment, 1st Infantry Division in April 1940. Shortly thereafter, he was re-assigned to the Division Military Police Platoon, which he commanded during the North African campaign. Rising through the ranks, he became Division G-5 (Assistant Chief of Staff - Civil Affairs) and served as Military Governor for first Aachen and later Bonn, Germany in 1944-1945.[12]

The 1st Infantry Division in Czechoslovakia

Since the middle of April, General Patton’s Third U.S. Army had been advancing along the 1937 German – Czechoslovak border. Though Third Army’s main effort was directed to occupy the rumored “National Redoubt” area of southern Bavaria and western Austria, its 2nd Cavalry Group, 90th Infantry Division and 97th Infantry Division were conducting limited operations across the border. By the end of April, the 2nd Cavalry Group had captured the border town of Asch and rescued several hundred Allied prisoners of war plus the famed Lipizzaner performing horses. The 97th Infantry Division had liberated the city of Cheb, and captured remnants of the Luftwaffe at the nearby Cheb airfield. The 90th Infantry had liberated the Flossenbuerg Concentration in Germany near the border. As April came to a close, the 1st Infantry Division was sent to the northwest part of Czechoslovakia to free up the 97th Infantry Division for employment further south. On 30 April, the 1st Infantry Division was transferred from VIII Corps to V Corps.[13]

By the evening of 30 April, First Army's V Corps had two divisions on the line on the Czechoslovak border. The 97th Infantry Division gained from Third U.S. Army was on the corps right tied in with XII Corps to the south-east. The 1st Infantry Division was on the corps left east of Asch and Cheb. East of Asch on the division left, the 26th Infantry Regiment had its 2nd and 3rd Battalions on the line with the 1st Battalion in reserve. In the division center, the 16th Infantry Regiment had its 1st and 2nd Battalions in Czechoslovakia with its 3rd Battalion in reserve in Selb. To the 16th Infantry's right was the 18th Infantry Regiment and its three battalions, all of which were on the line. The 6th Cavalry Group of VIII Corps was operating on the 1st Infantry Division’s left flank back in Germany.[14]

As stated earlier, tank and tank destroyer battalions rarely conducted operations as battalions. Thus, the companies of the 745th Tank Battalion and 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion were attached to support the infantry. The 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion’s companies were attached to each of the division’s three infantry regiments. A Company supported the 26th Infantry Regiment, B Company supported the 18th Infantry Regiment and C Company supported the 16th Infantry Regiment. The remainder of the battalion was attached to the Division Headquarters. Similarly, the 745th Tank Battalion assigned its companies out to support the infantry. A Company and the Mortar and Assault Gun platoons of Headquarters Company were attached to the 16th Infantry Regiment, and soon after, D Company was attached as well. B Company was attached to the 18th Infantry Regiment and C Company was attached to the 26th Infantry Regiment.[15]

Thus the armored support for the Big Red One’s infantry looked as follows:

· 16th Infantry Regiment:

o A/745th Tank Battalion

o D/745th Tank Battalion

o Assault Gun Platoon, Headquarters Company/745th Tank Battalion

o Mortar Platoon, Headquarters Company/745th Tank Battalion

o C/634th Tank Destroyer Battalion

· 18th Infantry Regiment:

o B/745th Tank Battalion

o B/634th Tank Destroyer Battalion

· 26th Infantry Regiment:

o C/745th Tank Battalion

o A/634th Tank Destroyer Battalion[16]

To complete the infantry regiments’ formation into Regimental Combat Teams (RCT), each regiment was assigned a field artillery battalion, and attachments from the 1st Engineer Combat Battalion, 1st Medical Battalion and other supporting divisional units.

For its first several days in Czechoslovakia, the 1st Infantry Division’s subordinate units relieved their counter-parts from the 97th Infantry Division, consolidated their positions, sent out reconnaissance patrols and conducted limited attacks. The 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion established a screen of sound and flash observation posts to locate German artillery positions. The 7th Field Artillery Battalion went into position west of the Czechoslovak border on 28 April and began supporting the 16th Infantry Regiment. The following day, the battalion, minus its Service Battery, moved into Czechoslovakia and took up firing positions. For the next several days, the 7th Field Artillery fired a number of missions in support of the 16th Infantry against such targets as enemy troop concentrations and vehicles. In three days, they fired over 349 rounds of 105mm artillery shells. On 2 May, 2nd Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment attacked and secured the towns of Hatzenreuth, Maiersreuth and Querenbach, capturing 120 prisoners in the process. On 3 May, 3rd Platoon of B Company, 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion destroyed a German armored car and caused many casualties among German infantry.[17]

Even though the Third Reich and the German Army were in their final days of existence, there were still groups of German soldiers who refused to admit defeat and end the war peacefully. A number of these groups happened to be opposing the 1st Infantry Division. On the night of 2-3 May, Captain James Barrow, and Technician 5’s Caldwell and Neihouse of the 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion Recon Company were captured by an enemy combat patrol. Efforts by the Recon Company and the 18th Infantry Regiment to locate and rescue the three soldiers were unsuccessful. The following day, the battalion’s Recon Company destroyed a Volkswagen and captured 38 Germans while searching for the three missing American soldiers.[18]

V Corps's intelligence officers identified numerous ad hoc German Army units as opposition. In the north was the 404th Training Division with companies of replacements, artillerymen fighting as infantry, and officer candidates. The 413th Training Division was opposite the 303rd Infantry Regiment. It was comprised of ad hoc kampfgruppen and engineers fighting as infantry. To the division's rear were the remnants of the 2nd Panzer Division. Farther south was another collection of ad hoc kampfgruppen, engineers and trainees. "None of the enemy units were very strong," stated the V Corps history. Resistance was light and consisted only of scattered road-blocks, and small arms and mortar fire.[19]

Staff Sergeant William Laird of the 5th Field Artillery Battalion later described the opposition that his division faced in Czechoslovakia. “The enemy force facing us was comprised of various units under the command of a General Benicke (Division Benicke),” he later recalled. “Some of the soldiers were of the best quality encountered in quite a while. They were from Milowitz, Czechoslovakia, a large officer candidate school.”[20]

The 5th of May 1945

Third U.S. Army’s commander General George S. Patton Jr. had been clamoring for permission to drive eastward with the intention of liberating western Czechoslovakia from Nazi control. In the early evening of 4 May 1945, he finally got the approval from Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower for an advance to the line running Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice. He was also to be prepared to advance further east upon orders from Eisenhower. To bolster his offensive, V Corps of First U.S. Army was transferred to Third Army that same day. Third Army now had four corps totaling over 540,000 soldiers with which to advance simultaneously east into western Czechoslovakia and south-east into Austria.[21]

On the morning of 5 May, Patton’s XII Corps and V Corps attacked eastward with their infantry divisions to open up routes for the armored divisions to follow. Combat Command A (CCA) of the 9th Armored Division was attached to the 1st Infantry Division for a drive east from the vicinity of Cheb with Karlovy Vary being the objective. The remainder of the 9th Armored Division was kept in reserve. The 1st Infantry Division advanced up to 14 kilometers on a front 48 kilometers wide and experienced some of the heaviest fighting of the liberation in the mountainous areas around Cheb. 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 18th Infantry Regiment were able to reach their objectives but 3rd Battalion encountered more determined resistance which delayed them from attaining their objectives until the early hours of 6 May. Numerous well defended road blocks were encountered and overcome. B Company, 745th Tank Battalion and soldiers of the 18th Infantry struck and overcame a determined group of Germans who were entrenched on the high ground north of Drenice. Nevertheless, casualties for the regiment that day were surprisingly light: 1 officer and 23 enlisted men wounded. The 7th Field Artillery Battalion fired just one mission that day, expending 23 rounds on a group of enemy soldiers late in the afternoon. Since German artillery fire was negligible, the 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion was used for rear area security and to transport captured Germans to prisoner of war enclosures.[22]

That day, 3rd Platoon, B Company, 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion and 3rd Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment ran into strong German resistance. At a range between fifty and one hundred yards, the platoon’s M10 tank destroyers fired off all of their 3-inch high explosive ammunition plus a large quantity of fifty-caliber machine gun ammunition. Four machine gun positions had to be physically run over by the U.S. tank destroyers to subdue them. One of the U.S. M-10s was hit by a German Panzerfaust anti-tank rocket and set on fire. The vehicle’s crew quickly extinguished the fire and the M-10 suffered only minor damage. When it was over, the platoon destroyed 12 machine guns, killed fifty of the enemy and wounded numerous others.[23]

The 6th of May 1945

Patton’s infantry divisions made considerable progress in their attacks on 5 May. Now it was the turn of his armored divisions. CCA of the 9th Armored Division was ordered to pass through the forward positions of the 1st Infantry Division and attack eastward to Karlovy Vary. In V Corps’s center, the 16th Armored Division was to pass through the 2nd and 97th Infantry Division and liberate the city of Plzen. Further south, the 4th Armored Division was to pass through the 90th and 5th Infantry Division and attack to the north-east towards Prague. The infantry divisions would then follow to consolidate the gains and mop up any bypassed resistance.

Early on the morning of 6 May, CCA 9th Armored Division passed through the forward positions of the 1st Infantry Division and attacked east. At several locations, the German forces put up resistance with anti-tank guns and infantry. CCA’s Task Force Engeman routed these forces, but suffered the loss of two light tanks and several casualties; including a tank driver who was killed.[24]

German resistance to the 1st Infantry Division’s advances was sporadic. In many places, the Germans put up strong resistance. The 1st Infantry Division lost several of its soldiers killed, including 2ndLt Elton Barker of the 16th Infantry Regiment. East of Drenice, stubborn German defenders held up the advance until being cleared out by tanks and tank destroyers. The attack of the 16th Infantry Regiment was preceded by a preparatory bombardment by the 7th Field Artillery Battalion. As the 16th Infantry attacked eastward, the 7th Field Artillery displaced forward twice to better support the infantry. The battalion expended a total of 81 rounds against German positions. Near the village of Schongrub, German soldiers attempted to oppose the advance of the 26th Infantry Regiment. Supported by tanks, elements of the regiment overcame the resistance, killing two, wounding two more and capturing twelve Germans. In other areas, German resistance was negligible or non-existent. The entire 655th Engineer Brigade with 1,500 men surrendered to the division. At the town of Kynzvart, five hundred Germans were captured.[25]

Attached to support the Big Red One’s three infantry regiments, many of the 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion and 745th Tank Battalion’s scattered platoons fought firefights against German soldiers still intent on resisting. 1st Platoon, A Company, 745th Tank Battalion and a team from the 16th Infantry Regiment ran into determined German resistance in the village of Klinghart. A civilian hit one of the U.S. tanks with a Panzerfaust. Despite the heavy small arms fire, Klinghart was ultimately secured.[26]

Throughout the day, Czech civilians greeted the American soldiers joyously. In the city of Plzen, thousands of civilians turned out to celebrate their liberation from the Germans by the 16th Armored Division, even in the midst of periodic fighting from diehard German resistance. For many veteran American soldiers, the experiences were reminiscent of those in France the preceding summer. Fighting as they were in the Sudetenland border region, the 1st Infantry Division did not enjoy such scenes of exuberant Czechs welcoming their liberators. Instead, they dealt with German soldiers and sullen Sudeten Germans.

The 7th of May 1945

After authorizing Patton to advance to the Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice line, General Eisenhower sent a message to the Soviet High Command informing them that he was considering an advance beyond that line to the west bank of the Vltava (Moldau) River. This storied river flows north through the heartland of Bohemia and Prague before joining the Elbe River in Germany.[27]

The following day on 5 May 1945, the Soviet High Command strenuously objected to Eisenhower’s proposal, as doing so would enable Patton’s army to liberate as least part of the Czechoslovak capital. With German resistance melting away before the Americans and Czechs partisans rising up against the Germans in Prague and numerous towns, Third U.S. Army could easily have reached Prague before the Soviets. As the Soviets were intent on imposing a Communist government in the post-war Czechoslovakia, the U.S. Army could not be permitted to liberate Prague. Accordingly, they prevailed upon Eisenhower to halt Patton at the Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice line.[28]

In responding to Eisenhower’s proposal, the Soviets falsely claimed a quid pro quo with Denmark. They insisted that they had allowed Eisenhower’s forces to liberate Denmark earlier that week. The fact was Field Marshall Sir Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group had successfully raced the Soviets to the Baltic Sea and thus prevented the Soviets from seizing Denmark. Even with Czech partisans in Prague desperately crying out for American help via radio and courier, Eisenhower would not permit Third Army to advance any farther east.[29]

On the morning of 7 May, Third U.S. Army was well positioned to resume the advance on Prague. In the north, CCA 9th Armored Division was just a few miles west of Karlovy Vary. In the center, 16th Armored Division had liberated Plzen and pushed several miles east. The 4th Armored Division had similarly advanced beyond the restraining line. In the south, the 5th Infantry Division was west of Ceske Budejovice. More importantly, only scattered organized resistance was being encountered. Rather, torrents of German soldiers and civilians were rushing westward to surrender to the Americans and thus escape being captured by the Soviets. That morning, many of Third Army’s units resumed their advance up to the restraining line. The orders to halt the eastward advance did not reach many of the units until late morning of 7 May.

On the morning of 7 May 1945, the units of 1st Infantry Division and its attached Combat Command A, 9th Armored Division resumed their attacks eastward. Their attacks had not proceeded far when word was received to halt. In mid-morning, CCA was ordered to halt just short of Karlovy Vary.[30]

Later that morning, the 1st Infantry Division and other Third U.S. Army units received the official word from General Eisenhower’s headquarters informing them the German High Command had surrendered early in the morning of 7 May. The provisions of the surrender agreement would take effect at 0001 on 9 May 1945. All offensive operations were to cease immediately.[31]

Also that morning, senior leaders of the German XII Corps surrendered not once but twice to the combined 1st Infantry Division / CCA 9th Armored Division force. In the first surrender ceremony, Major Henry T. Mortimer and Captain Cecil Roberts of CCA and a major from the 1st Infantry Division accepted the surrender of General Herbert Osterkamp and his corps at his headquarters with Captain Roberts formally accepting Osterkamp’s sword.[32]

Subsequent to Capt. Robert’s acceptance of that German corps’s surrender, Gen.Osterkamp surrendered his XII Corps again. This time, Gen. Osterkamp surrendered his corps to Brigadier General George A. Taylor, the Assistant Commander of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. Also present were Major Mortimer, Brig. Gen. Thomas Harrold - commander of CCA, 9th Armored, and several other 1st Infantry Division officers. Under interrogation, Osterkamp revealed that his corps had only about 2,200 soldiers in its three depleted divisions, and that altogether there were some 17,000 Germans in his area of responsibility. There was some difference of opinion over the exact terms of the German surrender but Gen. Taylor quickly prevailed. With little choice, Osterkamp accepted Taylor’s precise terms and surrendered his corps for the second time.[33]

VE-Day and Afterwards

VE-Day was the day that the war in Europe officially ended. Amongst U.S. soldiers serving in Czechoslovakia, the day was one of mixed emotions. There was relief that the war in Europe had finally ended. There was apprehension as many of these soldiers were scheduled to redeploy to the Pacific Theater for the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. There were concerns that some of the German soldiers would continue to fight; either from ignorance of the German surrender or outright defiance. There was a somber remembrance of comrades killed in battle.

This mixture of emotions was typified in the reaction of Staff Sergeant William Laird of the 5th Field Artillery Battalion. “We were in position east of Cheb and it felt like the best day in the world. I had survived,” Laird later recalled. “The last few days before VE Day and after VE Day were high tension days because we had to break contact with the enemy and we were never sure that they had ‘got the word.’”[34]

For Technical Corporal John Maney of the 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, VE-Day was a huge relief not only because the war in Europe ended but also because he, like many other long-serving veterans of the European Campaign, was not slated to redeploy to the Pacific Theater. “On VE Day I was in Susice and we were looking forward to going home. By then we knew we weren’t going to Japan,” he later recalled. “We each had enough points to get to go home and not be occupational troops either.”[35]

Many U.S. soldiers were too busy to celebrate the end of the war in Europe. “1st Division Headquarters was in Cheb (Eger) on VE Day,” recalled the division’s G-5 (Civil Affairs) Officer Lt. Col Thomas Lancer. “There was no celebration! We began to receive a great number of R.A.M.P.’s (Repatriated Allied Military Personnel), ie. freed p.o.w.’s.”[36]

At 1700 on the afternoon of VE-Day, the 26th Infantry Regiment held a church service in honor of the occasion. At least two of the old soldiers from each company were present. The regimental commander Col. Francis J. Murdoch, Jr. reviewed the regiment’s long combat history from Oran to Czechoslovakia. Taps was played in honor of the regiment’s deceased members.[37]

The 8th of May was also a day that many U.S. soldiers encountered the horrors of the Third Reich’s racial genocide. Soldiers of CCA 9th Armored Division and the 1st Infantry Division liberated Zwodau and Falkenau an der Eger, two sub-camps of the notorious Flossenbürg Concentration Camp liberated earlier by the 90th Infantry Division. Falkenau an der Eger held sixty prisoners. Zwodau held between 900 and 1,000 women prisoners. The latter had been set up by the German S.S. in March 1944 as a slave labor camp to produce air force equipment. The U.S. soldiers provided desperately needed food and medical care for the starving prisoners.[38]

CCA 9th Armored Division’s stay in north-western Czechoslovakia was brief. For the next week, CCA processed tens of thousands of surrendering German soldiers and civilians, then rejoined its parent division back in Germany.[39]

After the German surrender, the 1st Infantry Division was busily engaged in maintaining road blocks and control points, processing surrendering German soldiers and civilians, and guarding camps that held these German prisoners. With the massive flood of Germans fleeing the Soviet Army, this was a huge task for the Big Red One soldiers. A few days after VE-Day, the division set up a huge concentration area for surrendered German soldiers outside Cheb. Late on 11 May, the soldiers of the 7th Field Artillery Battalion were assigned to provide security for a section of the concentration area. Each day, one of the firing batteries augmented by personnel from Headquarters and Service Batteries guarded the battalion’s assigned sector. Meanwhile the other firing batteries remained on alert in case needed.[40]

The 745th Tank Battalion’s companies remained attached to the infantry regiments until 17 May. During this time, they performed occupation and security duties alongside their infantry counter-parts. On 17 May, the companies were relieved of their assignments to the infantry regiments and the battalion was re-assembled south-east of Cheb. The battalion was assigned to guard a sector of the division’s concentration area for German prisoners. The companies performed guard duties on a rotating basis for the remainder of their time in Czechoslovakia.[41]

For the remainder of the month, the 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion was employed in a variety of missions including transportation, security and patrolling. The battalion’s trucks were used to transport German prisoners and displaced persons to holding areas in the rear and to transport food and supplies to these holding areas. The battalion’s soldiers maintained road blocks and security posts and conducted patrols throughout their area of responsibility. During the month of May, the battalion captured some 1,148 German soldiers. The battalion was ultimately detached from its assignment to the 1st Infantry Division and remained in Czechoslovakia on occupation duties throughout the summer and fall of 1945.[42]

In many ways, the people of the newly liberated western Czechoslovakia expressed their appreciation to the U.S. soldiers. On 20 June 1945, President Eduard Benes held a ceremony in Plzen at which he presented a group of U.S. officers each with the Czechoslovak Military Cross. Among those receiving the medal from President Benes was Lt. Col Thomas Lancer.[43]

The 1st Infantry Division remained in north-western Czechoslovakia for about a month after VE-Day. In early June, the division was relieved by the 79th Infantry Division, and relocated to the area of Gunzenhausen, Germany to assume occupation duties there. A monument located on the outskirts of Cheb honors the 775 members of the division who were killed between February 1945 and VE-Day.[44]

The 1st Infantry Division remained in West Germany until 1955. For several years after the end of the war, the division was the largest American combat force in that country. Over the next several decades, the Big Red One fought in the Vietnam War, Operation Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom. The division is currently stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas.

Conclusion – From Oran to Czechoslovakia

During World War Two, the U.S. Army fought against Nazi Germany from the deserts of North Africa and the mountains of Italy to the forests and cities of the Third Reich itself and Czechoslovakia. The 1st Infantry Division --- the “Big Red One” – participated in most of these campaigns. The brunt of the U.S. Army’s casualties during these campaigns fell upon the infantry divisions, and more specifically, their front-line infantry soldiers. The 1st Infantry Division was no exception. From D-Day to VE-Day, the 1st Infantry Division fought in combat for 292 days. During this time, the division suffered a total of 29,005 battle and non-battle casualties and experienced a 205.9% turnover of personnel. Including its service in North Africa and Sicily, the 1st Infantry Division spent a total of 443 days in combat and suffered 4,325 killed and 15,457 wounded. Only two other divisions (the 45th Infantry Division and the 34th Infantry Division) spent more days in combat. The division’s fallen soldiers lay in U.S. military cemeteries in Tunisia, Italy, France, Belgium and Luxembourg. 2ndLt Elton Barker and nine other Big Red One who were killed liberating western Czechoslovakia are interred at the Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France.[45]

During its 443 days in combat, the 1st Infantry Division had fought on two continents. The division had liberated large areas of France, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia and captured large areas of Germany itself, including Aachen – the first German city to fall to the Allies. What the division began on the sands of Oran ended victoriously in the mountains of north-western Czechoslovakia.

*The author served as a Religious Program Specialist in the U.S. Navy Reserve for eight years, mobilizing and deploying twice to Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom. He served with the U.S. Marines MWSS-472 from January 2008 until June 2011 and served as Assistant Squadron Historian in 2009 and Squadron Historian in 2010/2011 as a collateral duty. He was honorably discharged in June 2011 as a Religious Program Specialist First Class (Fleet Marine Force).

[1] This brief history is from the First Division Museum website accessed on 29 July 2014 http://www.firstdivisionmuseum.org/history/history/default.aspx See also the U.S. Army Center of Military History website http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/cbtchron/cc/001id.htm accessed on 29 July 2014.

[2]Ibid.; H. R. Knickerbocker, et al. Danger Forward: The Story of the First Division in World War II. (Nashville, TN: Battery Press, 1980 reprint of 1947 edition.); The First - A Brief History of the 1st Infantry Division, World War II. (Cantigny, IL: privately published the Cantigny First Division Foundation, 1996), p.49. This is a re-print of a history printed by the division following WWII.;

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] U.S. Army. U.S. Army European Theater of Operations. Office of the Theater Historian. Order of Battle of the United States Army World War II: European Theater of Operations. Paris, France: December 1945, pp. 1-14. [Hereafter cited as US Army Order of Battle..; H. R. Knickerbocker, et al. Danger Forward: The Story of the First Division in World War II. (Nashville, TN: Battery Press, 1980 reprint of 1947 edition.)

[7] Ibid.; U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 745th Tank Battalion. “History of the 745th Tank Battalion, August 1942 to June 1945.” Privately published by the battalion in Nuernberg, Germany, 1945. Accessed online on 31 July 2014 at Howenstine, Harold D., "History of the 745th Tank Battalion, August 1942 to June 1945" (1945).World War Regimental Histories. Book 21. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/21

[8] 745th Tank Bn History.; U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 745th Tank Battalion. Report After Action Against Enemy – May 1945. 1 June 1945. Record Group (RG) 407, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Archives II, College Park, Maryland. This AAR also contains the battalion’s S-2 (Intelligence) and S-3 (Operations) Journals. All three documents will be cited hereafter as 745th Tank AAR.; Captain S. Scott Sullivan, USA. “Final Reunion: A Tribute to the Men of the 745th Tank Battalion.” Armor, (March-April 2000), pp. 8-11.

[9] U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion. After Action Reports – May 1945. Czechoslovakia: 1 June 1945. RG407, NARA. [Hereafter cited as 634th TD AAR.]

[10] US Army Order of Battle, pp. 498-501.; U.S. Army. 9th Armored Division. Combat Command A. After Action Report for May 1945. Germany: May 1945. RG407, NARA. [Hereafter cited as CCA 9AD AAR.]

[11] Ibid, pp. 1-14.

[12]William Laird. Staff Sergeant. Headquarters Battery / 5th Field Artillery Battalion / 1st Infantry Division. Letter to the Author. 20 April 1998.;Thomas F. Lancer, Colonel, USA (dec.). G-5 (Civil Affairs) Officer. 1st Infantry Division. Interview by Author, Fort Belvoir, VA. 15 May 1998. Col.Lancer passed away in 1999.

[13] For a general overview of the April operations, see U.S. Army. Third U.S. Army. After Action Report. 3 vols. U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center Archives. Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. [Hereafter the After Action Report is cited as TUSA AAR.] [Hereafter the Archives is cited as USAHEC Archives.]; Charles M. Province, Patton’s Third Army: A Chronology of the Third Army Advance August, 1944 to May, 1945. (NY: Hippocrene Books, 1992).; U.S. Army. V Corps. Operations in the ETO 6 January 42 - 9 May 45. (Germany: 1945). USAHEC Archives, pp. 445-446.[Hereafter cited as V Corps in ETO].;

[14] U.S. Army. V Corps. Headquarters. Letter of Instruction - 302200 April 1945. reprinted in V Corps in ETO, p. 446.

[15] 634th TD AAR.; 745th Tank AAR.

[16] Ibid.

[17] U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 18th Infantry Regiment. Regimental History of the 18th Infantry

for the Month of May, 1945. RG407, NARA.; U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 7th Field Artillery Battalion. Unit Journal for April 1945. RG407, NARA. See entries for 28-29 April 1945. Hereafter cited as 7th FA Unit Journal.; 634th TD AAR.; 745th Tank AAR.

[18] U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Battalion History. Printed privately by the battalion, 1945. USAHEC Archives.; 634th TD AAR.

[19] V Corps in ETO, p.447. This page contains a G3/G2 Situation Map as of 301800 April 1945.

[20] Laird Letter.

[21] For a more detailed analysis of the controversy surrounding the U.S. Army’s entry into Czechoslovakia, see Forrest C. “The Decision to Halt at the Elbe.” Command Decisions. ed. by Kent Roberts Greenfield. (Washington DC: Center of Military History, 2000), pp. 479-92. This article is primarily concerned with Berlin and the Elbe River stop line but also talks about the Prague controversy as well.; In addition, the Prague Liberation controversy was discussed at length in the author’s Masters Thesis for his Masters of Arts degree in American History from Monmouth University. The thesis examined the military, political and diplomatic conflicts that occurred in Czechoslovakia in 1945 between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. See Bryan J. Dickerson, “Czechoslovakia 1945 – Prelude to the U.S. / Soviet Cold War,” (Master’s Thesis, Monmouth University, 1999). [Hereafter cited as Dickerson Thesis.]

[22]V Corps in ETO, pp. 450.; The First, p.49. Regimental History of the 18th Infantry for the Month of May 1945., p. 1.; U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 18th Infantry Regiment. S-1 (Personnel) Journal. RG407, NARA.; U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 7th Field Artillery Battalion. Unit Report 1-31 May 1945. Czechoslovakia: 1 June 1945. RG407, NARA. Hereafter cited as 7th FA Unit Report MAY 1945.; 7th FA Unit Journal.; 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion History.

[23] 634th TD AAR.

[24] Dr. Walter E. Reichelt, Phantom Nine: The 9th Armored (Remagen) Division, 1942-1945. (Austin, TX: Presidial P, 1987.); CCA 9AD AAR.

[25] U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 26th Infantry Regiment. 3rd Battalion. Unit Journal. RG407, NARA. See entry for 6 May 1945.; 745th Tank AAR.

[26] 745th Tank AAR.; 634th TD AAR.

[27] Pogue, pp. 489-92; Dickerson Thesis.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] CCA 9AD AAR.

[31] Receipt of this message, often recorded verbatim, is found in various 1st Infantry Division and CCA, 9th Armored Division unit After Action Reports and Unit Journals.

[32] Major Henry T. Mortimer, S-3 (Operations) Officer. Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. Letter to Col. Cecil Roberts - 27 August 1987. Copy provided to the Author by Col. Roberts.; Cecil Roberts. Colonel, USA (dec.). Captain. S-3 (Operations) Officer. 14th Tank Battalion / Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. A Soldier From Texas. (Fort Worth, TX: Branch-Smith, Inc., 1978)., pp. 79-81. My thanks to Col. Roberts for sending me a copy of his memoirs.

[33] Ibid.; CCA 9AD AAR.

[34] Laird Letter.

[35] John F. Maney. Technical Corporal. Survey I Section / Headquarters Battery / 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion / V Corps. Letter to the Author. 13 January 2000.

[36] Lancer Interview.

[37] 3/26th Infantry Unit Journal. See entry for 8 May 1945.

[38] U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Holocaust Encyclopedia. “The 9th Armored Division.” Accessed on 5 August 2014 at http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10006146 ; U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Holocaust Encyclopedia. “The 1st Infantry Division.” Accessed on 5 August 2014 at http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10006132

[39] CCA 9AD AAR.

[40] 7th FA Unit Report MAY 1945.

[41] 745th Tank AAR.

[42] 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion History.

[43] Lancer Interview. Thomas Lancer returned home to the U.S. in November 1946 but returned to West Germany six months later. He served in Berlin during the 1948-49 Soviet blockade. He retired from the U.S. Army in 1962 at the rank of Colonel and passed away in June 1999.

[44] U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. 7th Field Artillery Battalion. Unit Report for 1-30 June 1945. Germany: 2 July 1945. RG407, NARA.

[45]Division casualty figuresare taken from U.S. Army. European Theater of Operations. History Section. Office of the Theater Historian. Order of Battle of the United States Army World War II European Theater of Operations. Paris: December 1945.; See also Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army from the Normandy Beach to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), pp. 280-83. Ambrose has taken the U.S. Army figures and put them into tables for each division involved that served with SHAEF. Total casualty figures for the 1st Infantry Division are from The First - A Brief History of the 1st Infantry Division, World War II., p. 97.; The 45th Infantry Division spent 511days in combat and the 34th Infantry Division spent 500 days in combat.

Post new comment